CANTUA CREEK, Fresno County — The water is too contaminated to safely drink, but residents of this farmworker community in the Central Valley pay $74 a month just to be able to turn on the tap at home.

Their bills are even higher if they use more than 50 gallons a day, a fraction of daily water consumption for the average California household. And when Fresno County finishes building a new well that has been planned for years, the price will increase again to cover the cost of treating manganese-laced water pumped from hundreds of feet below.

It’s a lot of money for families living off the minimum wage they earn in the nearby fields, so local leaders hoped to get help from a state fund created last year to address a crisis that has left the 275 residents of Cantua Creek and a million other Californians without clean water. Then the coronavirus pandemic hit, throwing the finances of the program into question right as it was launching.

The situation underscores just how difficult it will be for the state to reach its goal of bringing safe and affordable drinking water to all. At a meeting this month where the State Water Resources Control Board adopted its first spending plan for what was supposed to be a $130 million-a-year investment for the next decade, chair Joaquin Esquivel acknowledged that the economic downturn could set California back.

“The number of systems we can assume will be out of compliance, we’re really concerned that that’s even more, exponentially growing,” Esquivel said. “And the resources aren’t necessarily there, growing with it.”

For the residents of Cantua Creek who have fought the hardest to fix their polluted water, it can feel like they are the butt of a cruel bureaucratic joke — a community of workers growing the fruits and vegetables to feed a state that can’t supply them with clean water.

“It’s humiliating what they do to us,” Julia Mendoza, 50, a local activist who has traveled to Sacramento numerous times to lobby legislators and regulators for the new fund, said in Spanish. “We’re asking for the same right that everybody has: clean water.”

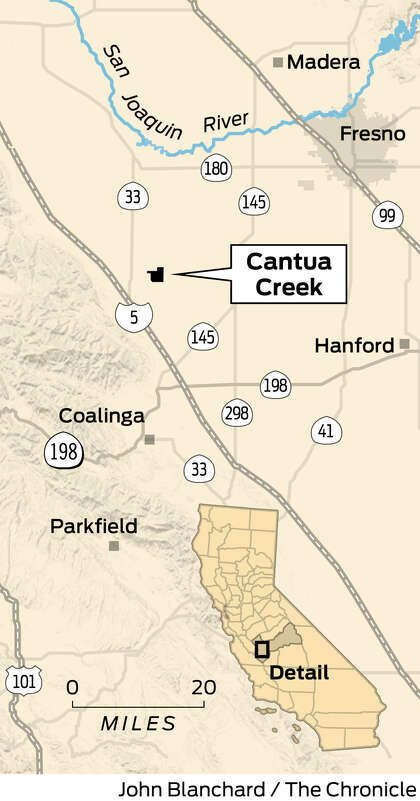

Surrounded by almond and pistachio groves 40 miles southwest of Fresno, Cantua Creek has a school, a small post office and a communal electric car. The water, supplied by the county and purchased from Westlands, the largest agricultural water district in the state, comes from the same irrigation canals that flow to fields of row crops.

It’s one of 310 public water systems in California that, as of March, were out of compliance with state standards on contamination levels or treatment techniques. The systems serve more than 920,000 people, though advocates say the number without safe drinking water is even higher when those who rely on private wells or small, unregulated systems are included.

The pollution is largely concentrated in agricultural communities in the Central Valley and Salinas Valley, where water is often contaminated by nitrates from pesticides, fertilizer runoff and dairy waste, and arsenic, which scientists believe is released into aquifers by overpumping. Cancer-causing chemicals have been found in the groundwater in some places.

“When you turn on the faucet in the morning, it has a very strong smell — like it’s rotten,” Blanca Gomez, 54, who has lived in Cantua Creek for more than two decades, said in Spanish.

Her family’s water bill approaches $90 a month just from bathing, cleaning and washing clothes. Gomez said that after doing a load of laundry, she uses the water from her washing machine for plants.

“All of the help goes to the rich, and they never take us poor people into account,” she said.

Five years ago, as the drought sent prices for surface water soaring, Cantua Creek voted down a $30 monthly rate increase and nearly had its water shut off by Fresno County. That caught the attention of the state, which stepped in with emergency assistance and has since been providing every home with eight 5-gallon jugs of water twice a month.

The supply gives people something to drink and cook with, though Gomez said it’s not enough for some large families. And residents still have to use the contaminated water flowing through their pipes for everything else, which they worry may be causing health problems.

“Our hair is falling out. Look at my hair. Most people living here, it’s falling out. Look, look,” Mendoza said, grabbing her head and pulling loose several graying strands. “This is not a solution. We want a solution to our water.”

The state’s Safe and Affordable Drinking Water Fund, created last year to help communities without the resources to build new water systems or maintain old ones, was meant to be that solution. But with the pandemic dragging California’s economy into recession, it’s unclear how much the state will be able to help.

After a multiyear push to tax residential water users and fertilizer sales fell short in the Legislature, Gov. Gavin Newsom turned to an unconventional source to create the fund: the state’s cap-and-trade auction for large greenhouse gas polluters, which is supposed to pay for programs that reduce emissions. Under a law signed a year ago, the fund would receive 5% of annual cap-and-trade revenue, up to $130 million, for the next 10 years.

To fully fund the program, the quarterly auctions would need to raise an average of $650 million — a total regularly exceeded before the pandemic hit. The first three auctions of the last fiscal year brought in an average of about $694 million.

Then in May, California made just $24.5 million from its first post-pandemic auction, down 97% from the same period in 2019. While that was not an immediate threat to clean drinking water projects, which received full funding last year, it raised alarms for advocates who worry about the sustainability of a program that could fluctuate wildly. The next few auctions, likely to be held during pandemic times, could bring equally grim results.

“We’ve been pretty clear that in the long term, we don’t think that the cap-and-trade revenue is the right solution,” said Michael Claiborne, a senior attorney with Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, one of the organizations that lobbied for the fund.

There is not likely to be an alternative any time soon. The law includes a backstop from the state general fund, beginning in 2023, but California has nothing to spare this year after pulling nearly every string it could to close a projected $54 billion budget deficit. Returning to the original idea of a dedicated clean-water fee on customers and agribusiness seems like an even longer shot.

“Even if the Legislature had a stomach to pass a tax right now, which I don’t think they do, the money from farmers wouldn’t be there,” said Emily Rooney, president of the Agricultural Council of California, which represents about 15,000 growers.

Rooney said supporters on all sides are banding together to seek federal dollars and other resources: “I do believe there are pots of money available to solve the crisis.”

The Legislature has to approve a spending plan for 2020-21 cap-and-trade revenue when it returns Monday for the final month of its session. Leaders have indicated that the clean drinking water program will be a priority for whatever funding is ultimately available, though advocates expect it will wind up short of the full $130 million.

Sen. Bill Monning, a Democrat from Carmel who carried legislation to create the fund, said the budget problems amount to a blip in what was always going to be a long-term effort to fix California’s water contamination crisis.

“If there’s a stall, it will be that,” he said. “It won’t be a cessation.”

But it does leave communities that have been waiting for clean water hanging in the balance a while longer.

This spring, after years of studies and site tests and stops and starts, Fresno County dug a new well in Cantua Creek. Located across the street from Gomez’s bright-blue home and the electric vehicle charging station, it won’t yield water until the county builds pumps and a manganese treatment plant.

Faced with uncertainty about whether the state will have money available to help pay for the project, Mendoza recalls the saying, “El que persevera alcanza.” The rough translation is, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

“It’s been a fight,” she said. “We have to have that hope.”

Alexei Koseff is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: alexei.koseff@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @akoseff

"had" - Google News

July 25, 2020 at 06:00PM

https://ift.tt/2BybgR6

California had a plan to bring clean water to a million people. Then the pandemic hit - San Francisco Chronicle

"had" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KUBsq7

https://ift.tt/3c5pd6c

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "California had a plan to bring clean water to a million people. Then the pandemic hit - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment