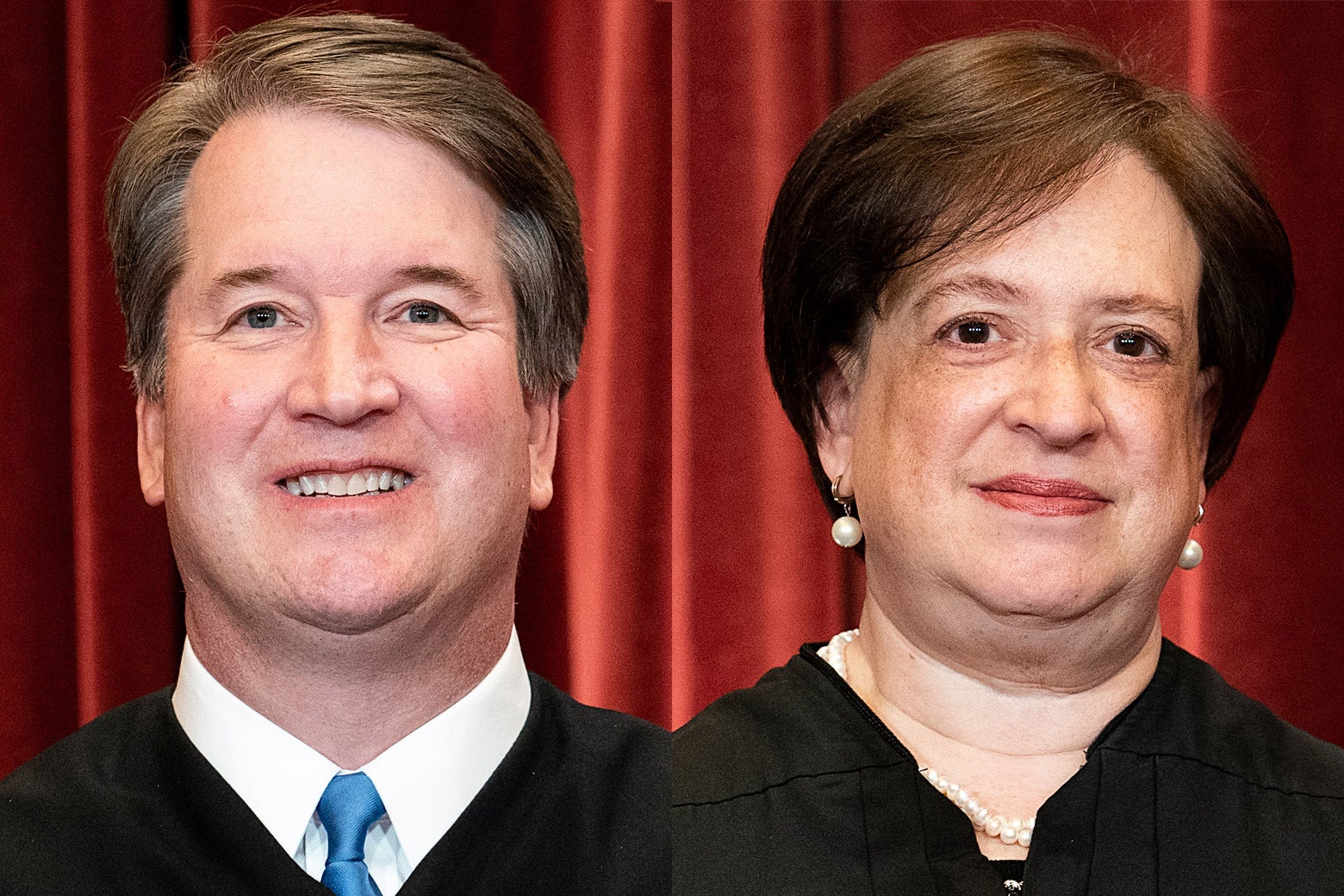

Last year, the Supreme Court issued a landmark decision in Ramos v. Louisiana, prohibiting nonunanimous convictions of criminal defendants. Under the Constitution, the court declared, a split jury verdict is “no verdict at all.” On Monday, however, the court walked back this declaration. In Edwards v. Vannoy, the conservative majority held that Ramos does not apply retroactively—that is, to defendants who have already been convicted by split juries. The court then took the extraordinary step of overturning precedent that had allowed retroactive application of new decisions. No party asked the Supreme Court to reverse this precedent; the question was not briefed or argued. But Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s majority opinion reached out and grabbed it anyway, slamming the courthouse door on convicted defendants seeking the benefit of a new Supreme Court decision.

Kavanaugh’s overreach drew a sharp dissent from Justice Elena Kagan, joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer. But there is more to Kagan’s dissent than her usual rejoinders and witticisms. The justice also responded to Kavanaugh’s charge that she is a hypocrite, criticizing his cynical view of “judging as scorekeeping.” It appears that Kagan is losing patience with Kavanaugh’s efforts to “insulate” himself from criticism with rhetoric that obfuscates the cruel consequences of his decisions.

Edwards dashes the hopes of criminal defendants who thought they received a lifeline in Ramos. By any standard, Ramos was a momentous decision: In his opinion for the court, Justice Neil Gorsuch declared that a jury verdict does not qualify as a conviction under the Sixth Amendment unless it is unanimous. At that time, only Louisiana and Oregon still allowed split verdicts, and the Ramos decision applied to defendants in both states who had not yet received a “final criminal judgment.” This group included defendants who had not yet received a trial as well as defendants contesting nonunanimous convictions on “direct appeal,” meaning they had not finished their first round of appeals. Those folks can get a new trial.

But what about the many more defendants who had previously appealed their nonunanimous convictions and failed to win relief? These individuals can only launch a “collateral appeal,” or an attack on the legality of a final conviction, to demand a new trial. Both Congress and the Supreme Court have strictly limited collateral appeals, because they prefer that “final judgments” remain final. (They are also afraid that these appeals will expose egregious injustices that undermine the integrity of countless convictions, but that’s a conversation for another day.) In 1989’s Teague v. Lane, the Supreme Court identified two types of decisions that apply retroactively on collateral review: new substantive rules (like those protecting some individual liberty) and new “watershed” rules of criminal procedure. (A quintessential example of such a “watershed” rule is the right to court-appointed counsel established in 1963’s Gideon v. Wainwright.) The question in Edwards was whether Ramos announced such a rule.

It did not, Kavanaugh held in his opinion for the court. But he went much further than that, writing that Ramos did not announce a “watershed” rule because there are no watershed rules. The Supreme Court’s decision in Teague was wrong, according to Kavanaugh; it is “moribund” and must be overturned. SCOTUS has not identified a watershed rule since Teague, he reasoned, so they must not exist.

Thus, in a single page, Kavanaugh wiped out decades of precedent allowing new rules of criminal procedure to apply retroactively. And he did not offer the usual justifications that the court provides when reversing its past decisions. Instead, he asserted that he was actually helping criminal defendants: Overturning “a theoretical exception that never actually applies,” Kavanaugh wrote, would dispel the “false hope” provided to defendants by Teague. “No one can reasonably rely on an exception that is non-existent in practice,” he insisted, “so no reliance interests can be affected by forthrightly acknowledging reality.”

Edwards put Kagan in a tough position. The justice is committed to stare decisis, or respect for precedent, and dissented from Ramos because it overturned precedent going back to 1972. On Monday, though, Kagan embraced the decision she once opposed: “Now that Ramos is the law, stare decisis is on its side,” she explained. “I take the decision on its own terms, and give it all the consequence it deserves.” She then listed the flaws in Kavanaugh’s analysis—chiefly by quoting Kavanaugh (who joined Ramos and wrote separately defending it) and Gorsuch (who authored the majority opinion in Ramos). The two justices called Ramos “vital,” “essential,” “indispensable,” “fundamental,” “momentous,” and more.

“If you were scanning a thesaurus for a single word to describe the decision,” Kagan noted, ”you would stop when you came to ‘watershed.’ ” She continued:

The majority doesn’t contest anything I’ve said about the foundations and functions of the unanimity requirement. Nor could the majority reasonably do so. For everything I’ve said about the unanimity rule comes straight out of Ramos’s majority and concurring opinions. Just check the citations: I’ve added barely a word to what those opinions (often with soaring rhetoric) proclaim.

The justice went on to explain why Ramos fits perfectly within Teague, and why that precedent is worth preserving. “The majority gives only the sketchiest of reasons for reversing Teague’s watershed exception,” Kagan wrote. “Seldom has this court so casually, so off-handedly, tossed aside precedent.” And it did so even though “no one here asked us to.” The result is fundamentally unfair: Thousands of people will remain behind bars, some for life, because they happened to exhaust their direct appeals before Ramos came down.

Kavanaugh, stung by the criticism, responded by accusing Kagan of posturing. “It is of course fair for a dissent to vigorously critique the court’s analysis,” he scolded. “But it is another thing altogether to dissent in Ramos and then to turn around and impugn today’s majority for supposedly shortchanging criminal defendants.” Kavanaugh wrote that “criminal defendants as a group are better off under Ramos and today’s decision, taken together, than they would have been if Justice Kagan’s dissenting view had prevailed in Ramos.”

In her final footnote, Kagan responded to this charge. Kavanaugh’s claim that he is “properly immune from criticism” because of Kagan’s position in Ramos “is surprising,” she wrote. She went on:

It treats judging as scorekeeping—and more, as scorekeeping about how much our decisions, or the aggregate of them, benefit a particular kind of party. I see the matter differently. Judges should take cases one at a time, and do their best in each to apply the relevant legal rules. And when judges err, others should point out where they went astray. No one gets to bank capital for future cases; no one’s past decisions insulate them from criticism. The focus always is, or should be, getting the case before us right.

It’s worth parsing Kagan’s words here, because they are chosen carefully, and they hit their mark. Since joining the bench, Kavanaugh has sought to frame himself as an honest broker who empathizes with the parties he rules against. In Bostock v. Clayton County, he spent 27 pages explaining why the Civil Rights Act does not protect LGBTQ employees but closed by praising the “exhibited extraordinary vision, tenacity, and grit” of gay Americans. In the peace cross case, Kavanaugh voted to uphold a huge cross on public land while expressing his “deep respect for the plaintiffs’ sincere objections,” as well as their “distress and alienation.” In the DACA case, Kavanaugh empathized with Dreamers who “live, go to school, and work here with uncertainty about their futures,” then voted to let them be deported. And last month, in Jones v. Mississippi, he restored juvenile life without parole while highlighting “moral and policy arguments” for the early release of juvenile defendants that can be presented “to the state officials authorized to act on them.”

The conservative Josh Blackman has condemned Kavanaugh’s habit as “virtue signaling.” While she comes at it from a very different perspective than Blackman, Kagan’s dissent in Edwards echoes this allegation. It seems that, in her view, Kavanaugh is trying to “bank capital” by flaunting his empathy, as if he can mitigate the unjust effects of his most conservative opinions. His deep concern for the losing party should offset the actual ramifications of his actions. When he supports a liberal outcome, even better: He can defend himself against future charges of callousness by pointing to his past votes. In doing so, Kavanaugh seeks to “insulate” himself from criticism when he writes a decision like Edwards, which will keep people locked up on the basis of “no verdict at all.”

In his superb profile of Kavanaugh, the Atlantic’s McKay Coppins reported that Kagan “launched a quiet charm offensive” to win over the justice after his confirmation. And indeed, until recently, Kagan rarely aimed her sharpest arrows at him. Her tone changed during the election, after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died, when she ruthlessly undermined his error-ridden opinion defending voter suppression. (He later issued a correction.) Kagan’s dissent in Edwards confirms that the justice is done trying to nab Kavanaugh’s vote by pulling punches. Indefinitely confined to a three-justice minority, Kagan knows her influence is largely limited to dissents. If she cannot bring Kavanaugh around to her side, she might as well show the rest of us the cynicism at the heart of his jurisprudence.

"had" - Google News

May 18, 2021 at 04:15AM

https://ift.tt/3yjrp5l

Elena Kagan Has Had Enough of Brett Kavanaugh’s Judicial “Scorekeeping” - Slate

"had" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2KUBsq7

https://ift.tt/3c5pd6c

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Elena Kagan Has Had Enough of Brett Kavanaugh’s Judicial “Scorekeeping” - Slate"

Post a Comment